Exploring Induction Heads

An investigation of in-context learning and induction head behavior in BERT.

Motivation

Why study induction heads in BERT? In-context learning is a phenomenon observed in language models where the models are better at predicting tokens later in the context than earlier ones, even without additional training [1]. In conjunction with observing this phenomenon, previous research has hypothesized that induction heads are the mechanism for the majority of in-context learning [1]. Despite the importance of induction heads, their specific behaviors and why they develop remains a largely unanswered question.

Current literature largely focuses on in-context learning in unidirectional models like GPT. Induction heads have not been previously explored in bidirectional models like BERT; however, the emergent in-context learning behaviors and induction heads found in unidirectional transformer models, as well as cases of prompt-based learning seen in bidirectional models like T5 and BERT [2], point toward the potential existence of induction heads in BERT.

In particular, in this work, we focus here on behavioral induction heads (rather than mechanistic ones), defined as attention heads that exhibit prefix matching or copying behaviors observed through attention patterns on out-of-distribution sequences made of repeated random tokens (RRT) [3].

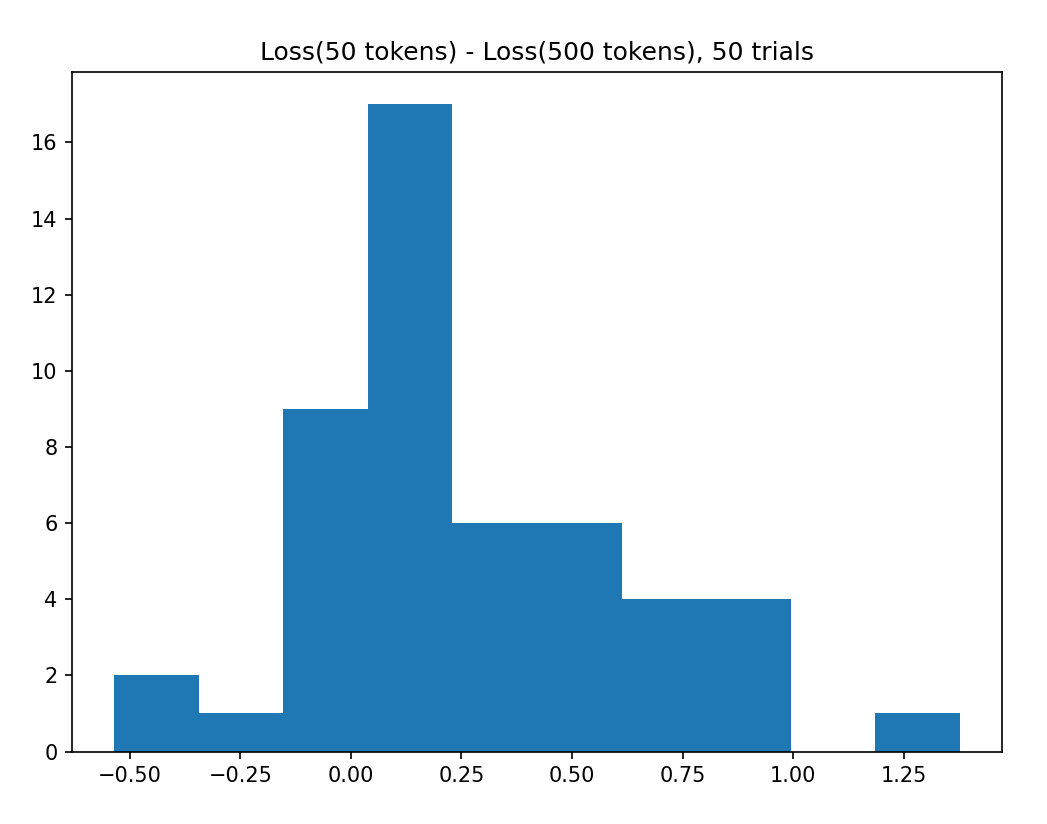

Confirming in-context learning in BERT. We first run an initial experiment to check whether BERT exhibits in-context learning. For unidirectional transformer models, Olsson et al. [1] define an in-context learning (ICL) score as the loss of the 500th token in the context minus the loss of the 50th token in the context, averaged over several dataset examples. We replicate a similar heuristic for BERT, where we set the ICL score as the average difference in token-prediction loss for two varying context lengths of 50 and 500:

\[\textrm{ICL Score} = Loss(50 \textrm{-token context}) - Loss(500 \textrm{-token context})\]We tokenized the Hugging Face Wikipedia-simple dataset, and selected the first 50 and 500 tokens of an article as the two model contexts. We then chose a random token to mask from each context, used BERT to predict the masked token, and computed the loss. Figure 1 displays the ICL scores computed across 50 trials. The mean difference was 0.23, demonstrating a noticeable difference in performance between the two contexts and a signal of in-context learning in BERT.

Methods and Experiment Setups

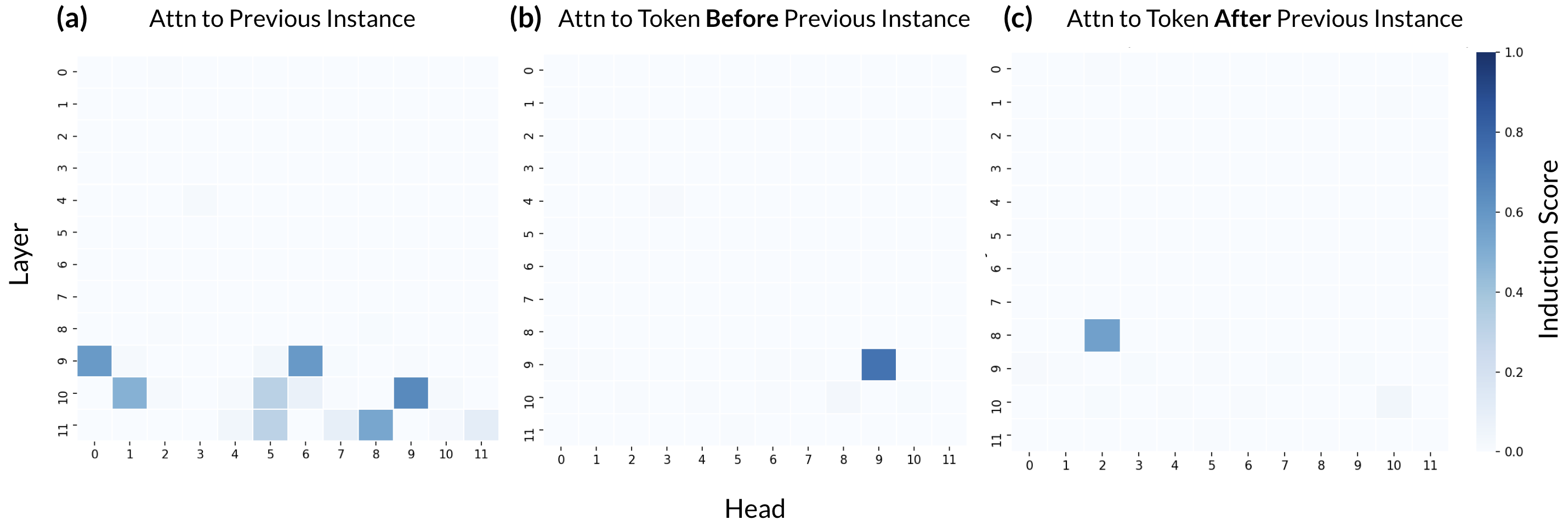

To visually explore induction heads in BERT, we drew particular inspiration from the Induction Mosaic [4], a mosaic heatmap of the induction heads in 40 open-source transformer models. In the Induction Mosaic, induction scores were calculated by giving each model a sequence of repeated random tokens and measuring the average attention each head paid to the token after the previous copy of the current token.

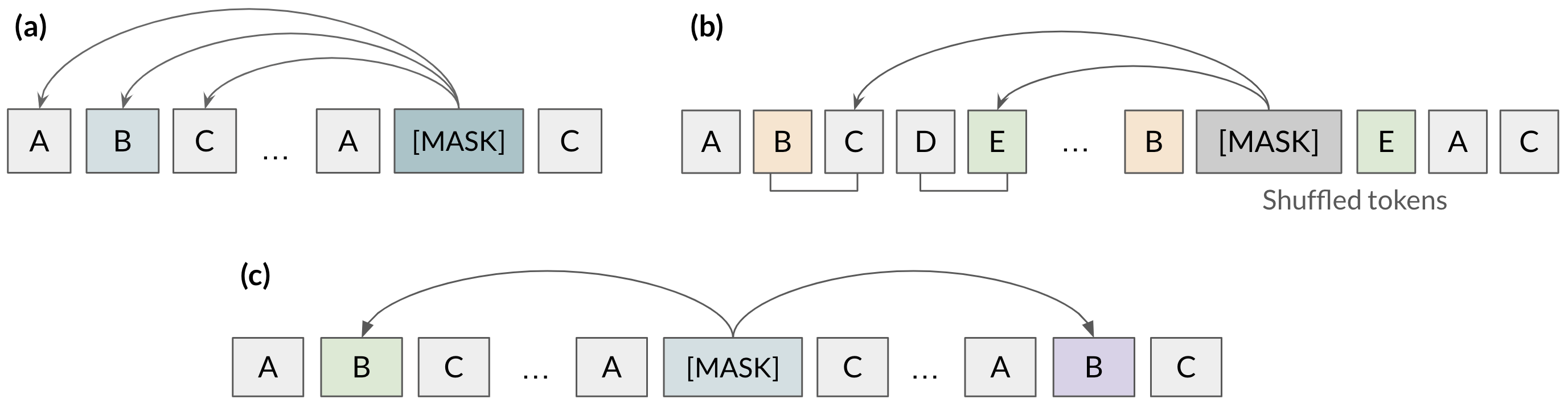

We employ a similar experimental setup for exploring potential induction heads in BERT. First, we generate a sequence of 200 random tokens. We then repeat this sequence of tokens, with several experiment variations (standard, shuffled, repeated on both sides) as shown in Figure 2, to generate a set of random repeated tokens (RRT). We randomly select a token from the second set of random tokens to mask and then pass the masked RRT to the BERT model. From here, we observe the output attention placed from the masked tokens to “inductive” areas, such as the previous instance of the masked token and the tokens before/after the previous instance.

For a specific attention head, the average output attention to these inductive tokens, computed across 50 trials, is defined as the induction score. The induction score represents the likelihood for a specific attention head to be an induction head. We generate an “induction map” visualization which displays the induction scores for each attention head as a heatmap.

Results

Induction Maps: Standard Setup. We first generated heatmaps for the standard RRT experiment setup, depicted in Figure 2a, where attention values were observed from the [MASK] token to the previous instance and the tokens before and after the previous instance. The induction maps for these three cases are shown in Figure 3. In the first heatmap, we see that there are several attention heads with strong induction scores. Interestingly, note that all of these high-scoring heads are located in the last three layers. In the cases of observing the attention to the tokens before/after the previous instance, we see in each case that only one head (layer 9 head 9 for the token before and layer 8 head 2 for the token after) gives a strong induction score.

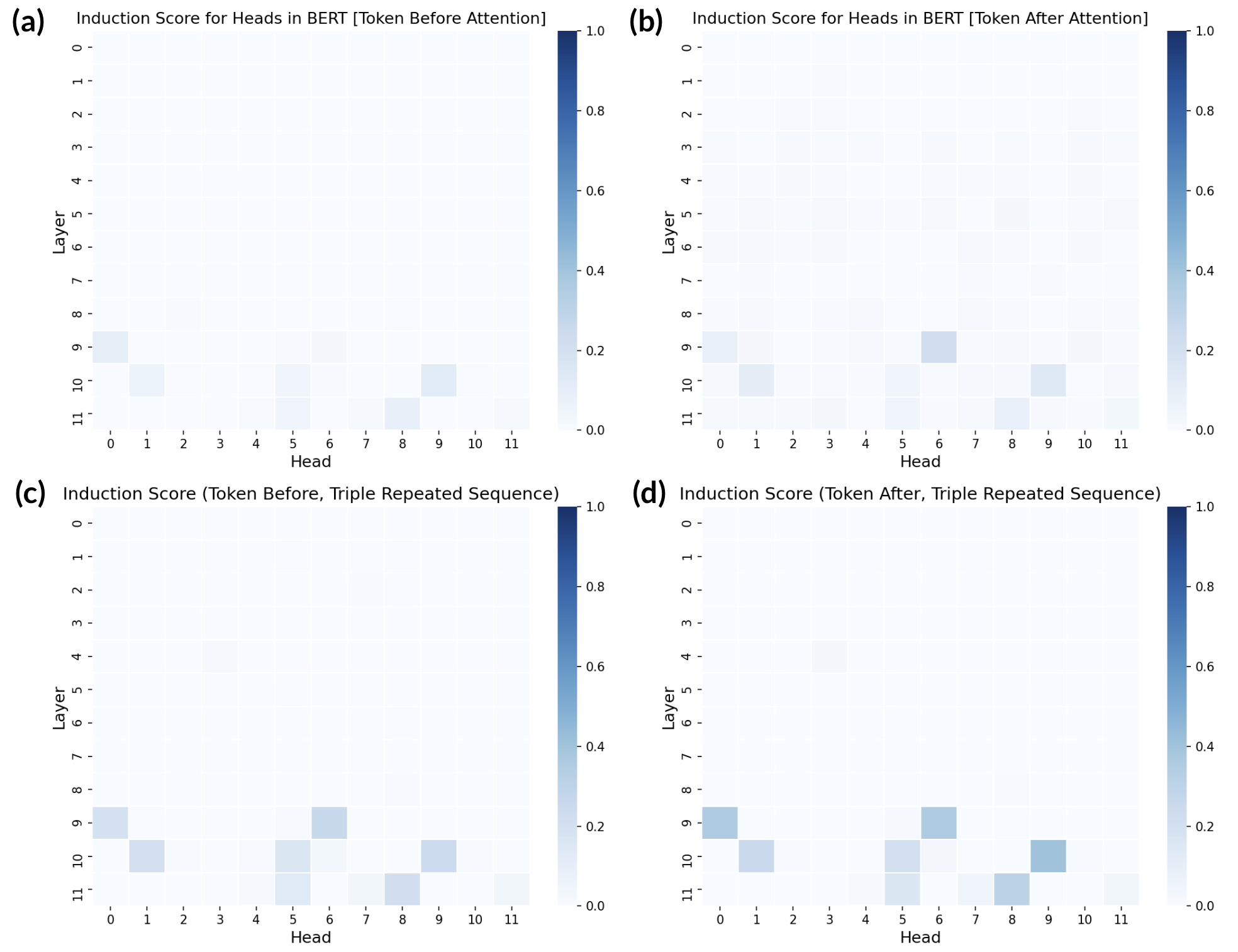

Induction Maps: Variations. We also generated induction maps for the shuffled and bidirectional RRT experiment setups. For the shuffled version, we observed attention to the token after the previous instance of the token before the masked token (Figure 4a) and the token before the previous instance of the token after the masked token (Figure 4b). Both yield faint induction scores, but interestingly for the same heads as those in Figure 3a. For the bidirectional attention experiment, we observe attention to the previous and later instances of the masked token, shown in Figures 4c and 4d which again yields the same induction patterns as Figure 3a, but attention is now spread across the two instances.

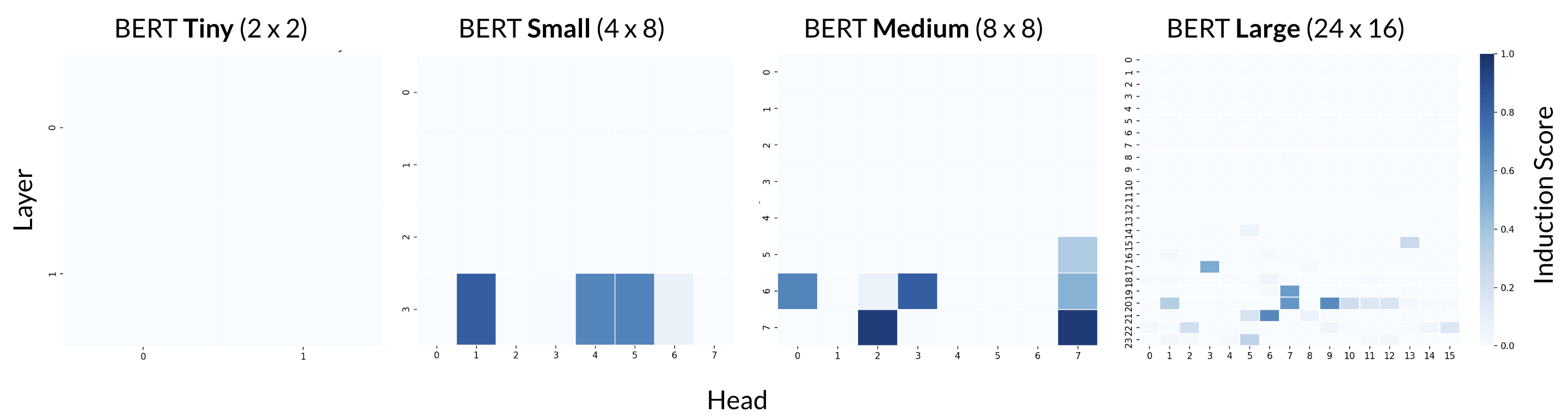

Do induction heads always appear in later layers? We observed that all the attention heads with high induction scores occurred in later layers, and were curious to explore this pattern more. To investigate this further, we ran the same RRT experiment on four BERT model variations that have different sizes: Tiny (2 x 2), Small (4 x 8), Medium (8 x 8), Large (24 x 16). The induction maps for each of these models are displayed in Figure 5. For the Small, Medium, and Large BERT models, we notice the same pattern that the high-scoring attention heads all occur in the later layers.

Similar trends of induction heads appearing in later layers are also observed in unidirectional models like GPT, as shown in the Induction Mosaic [4]. A potential hypothesis for why this may be the case is that if induction heads mostly serve to directly predict the next tokens, it makes sense that they’re in later layers as there is less distance to communicate information down.

Future directions. The results from our initial investigation into induction heads in BERT pose several interesting questions and possible future avenues of exploration. Future work could look into the effects of model ablation, in particular ablating heads with a high induction score (such as L9H9 and L8H2). An interesting question to explore here would be whether a ``backup” induction head would appear if we removed these heads or zeroed out their weights, a behavior which was noted in GPT-2 [5]. Another distinct pattern worth investigating is how induction heads only occur in the latest layers, which could point towards existence of heads performing tasks beyond just direct repetition and copying. Potentially, individual heads could serve unique purposes, such as focusing on language translation, by attending to specific types of tokens. Finally, some other experiments to run would be masking more than one token and observing joint attention, and also exploring the relationship between tokens and words and how attention is distributed amongst them.

References

[1] C. Olsson, N. Elhage, N. Nanda, N. Joseph, N. DasSarma, T. Henighan, B. Mann, A. Askell, Y. Bai, A. Chen, et al. In-context learning and induction heads. Transformer Circuits Thread, 2022.

[2] A. Patel, B. Li, M. S. Rasooli, N. Constant, C. Raffel, and C. Callison-Burch. Bidirectional language models are also few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14500, 2022.

[3] A. Variengien. Some common confusion about induction heads.

[4] N. Nanda. Induction Mosaic.

[5] K. Wang, A. Variengien, A. Conmy, B. Shlegeris, and J. Steinhardt. Interpretability in the wild: a circuit for indirect object identification in GPT-2 small. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.00593, 2022.

This project was conducted at the Insight + Interaction Lab at Harvard University in collaboration with Catherine Yeh under the supervision of Professor Martin Wattenberg and Professor Fernanda Viégas.

Questions or thoughts?Email me at cynthiachen@college.harvard.edu.